Valley of Rubies:

A Rare Visit To A Legendary Source Reveals Hard Times In A Hard Land

This article originally appeared in the Volume 17, No.2, March/April 2004 issue of Colored Stone magazine (www.colored-stone.com). Reprinted with permission. Text and photos by JB

Tucked into upper Myanmar about 650 kilometers (400 miles) from Yangon (formerly Rangoon), the country's famed Mogok stone tract has been the premier source for fine corundum (i.e., rubies and sapphires) for more than 800 years.

The valley isn't a tourist attraction. It's never been allowed to be. Throughout Myanmar's history, the region has been largely inaccessible, jealously guarded by kings, tribal chieftains, invading armies, and, today, Myanmar's ruling military junta. After gem mining was nationalized by the government in 1963, travel to Mogok became even more severely restricted than it had been in the past. Since then, few non-Myanmar nationals have been allowed to visit, for fear that the gem buyers would set up direct buying connections at the source The valley isn't a tourist attraction. It's never been allowed to be. Throughout Myanmar's history, the region has been largely inaccessible, jealously guarded by kings, tribal chieftains, invading armies, and, today, Myanmar's ruling military junta. After gem mining was nationalized by the government in 1963, travel to Mogok became even more severely restricted than it had been in the past. Since then, few non-Myanmar nationals have been allowed to visit, for fear that the gem buyers would set up direct buying connections at the source

During the past 14 years, the government of Myanmar has on several occasions briefly opened the area to foreigners, only to close it again without warning. The more difficult it has been to get to Mogok, the more its legendary status has grown.

I began applying for permission from the Myanmar government to visit Mogok several years ago. In November 2002, after several false starts, the door to Mogok finally opened for myself and two fellow gem dealers from Thailand.

MYANMAR ON MY MIND

Located in southeastern Asia, Myanmar borders the Andaman Sea and shares boundaries with Bangladesh, India, China, Laos, and Thailand. Slightly smaller than Texas in area, it has a population of 45 million.

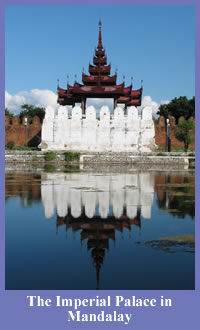

My journey to Mogok started with a one-hour flight from Bangkok to Yangon, the capital city of the Republic of Myanmar. The next morning, we flew from Yangon to Mandalay. In Mandalay, we met our military escort, which consisted of a driver, a "tour guide," and a stern military intelligence officer who was in charge of our party.

The drive from the airport in Mandalay to Mogok may be one of the loneliest in all of Southeast Asia. For a time, the one-and-a-half-lane tarmac runs parallel to the Irrawaddy River. We came to the first of five military checkpoints several miles north of Mandalay. Without our military escort, the journey to Mogok would have ended there. With it, we were allow to continue on the heavily-watched road.

After we passed the first checkpoint on our six-hour, 125-kilometer (78-mile) drive, we seemed to take a step back in time. For the first four hours, we passed monotonous small villages and farms on flat, sparsely populated land. I saw more bicycles and oxcarts than cars. After we passed the first checkpoint on our six-hour, 125-kilometer (78-mile) drive, we seemed to take a step back in time. For the first four hours, we passed monotonous small villages and farms on flat, sparsely populated land. I saw more bicycles and oxcarts than cars.

The road then began to twist and turn, taking us steadily higher into the mountains. We passed timber plantations and picturesque hill villages set into deep jungle. After a while, we saw some mining operations, the first sign that we had entered gem country. For the last few miles, we wound through narrow mountain roads with steep drop-offs on one side and 15-foot daisies on the other.

Then, suddenly, we rounded the last bend on the road to Mogok and were greeted by an incongruous 20-foot-high sign that read "Welcome to Rubyland."

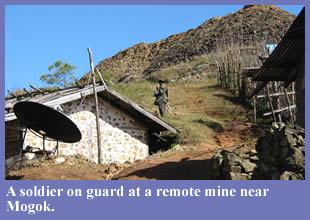

For the next five days we were closely monitored by our "tour guides." In the morning, our escort would arrive at sunup to drive us to our intended destination for the day and never let us out of their sight until we went to bed at night. These constant companions were friendly and courteous, but it was always clear that their main job was surveillance. We were told that up to 20 percent of the value of anything we bought had to be paid to the government representatives.

Everywhere we went, we were greeted by surprised and curious looks. If we stopped to eat or buy supplies at a roadside shop, a crowd would quickly gather just to stare at us. I had the distinct impression that many of the children had rarely or never seen a Caucasian. Yet the people were, without exception, friendly. Everywhere we went, we were greeted by surprised and curious looks. If we stopped to eat or buy supplies at a roadside shop, a crowd would quickly gather just to stare at us. I had the distinct impression that many of the children had rarely or never seen a Caucasian. Yet the people were, without exception, friendly.

Mogok has a peaceful, diverse population, a mix of various ethnic groups from around Myanmar and its neighboring countries. These people have been getting along and mining for a long time, which made the warm interest they showed in us seem perfectly natural.

QUANTITY WITHOUT QUALITY

Ruby is indisputably the most important of Mogok's gems, followed by blue sapphire, red spinel, and peridot. But many other gem species are found there also.

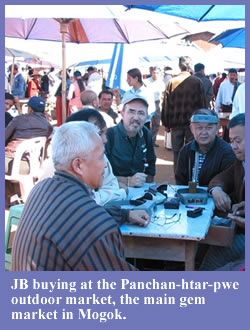

To get a feel for Mogok's riches, you can visit the Panchan-htar-pwe outdoor market, where hundreds of people come daily to buy and sell gems and minerals. It is a strange sight, almost festive, with scores of beach-sized, pink and blue umbrellas.

Under these umbrellas are small wooden tables and stools where buyers sit and wait for brokers, dealers, and miners to come and offer their gems. Bidding is risky, because the light filtering through the umbrellas makes rubies appear redder and sapphires bluer than they actually are. Under these umbrellas are small wooden tables and stools where buyers sit and wait for brokers, dealers, and miners to come and offer their gems. Bidding is risky, because the light filtering through the umbrellas makes rubies appear redder and sapphires bluer than they actually are.

As requested, I was shown ruby and blue sapphire, as well as numerous shades of fancy-color sapphire from pink to yellow in tones from deep to light. But Mogok is about far more than corundum. I was shown the full spectrum of spinel colors (mostly red, pink, and blue), as well as peridot, blue kyanite, tourmaline of various colors, danburite, amethyst, topaz, green zircon, fluorite, kornerupine, and aquamarine. The vast array of gems was impressive.

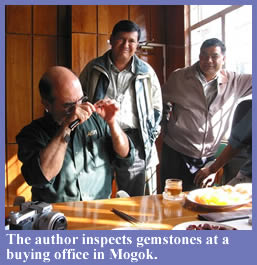

However, I was not impressed with the quality of the goods I saw - at least, not those put on sale at the outdoor markets. To be fair, I had been forewarned by some of our contacts that to find finer goods, you have to be invited into homes or offices.

Later, I saw a small amount of gem-quality material at a mining office. But for the most part, I found the shortage of fine gems almost as great behind closed doors as in the public square. Whenever I asked mine owners and dealers about it, they always said the same thing: The mines of Mogok are simply not producing very much today. At one mining office, I was told there were 1,000 mines in the area several years ago. According to this source, a third-generation Nepalese and a partner in several mines, only 600 mines are still being worked. Even with Mogok's low-cost labor, many mines are closing because they are unprofitable.

A FIRSTHAND PEEK

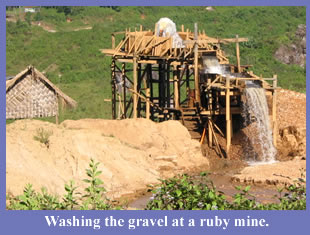

Gem mining at Mogok can be found everywhere - from the valley floor to the mountaintops and anywhere in between. Although mining techniques are relatively primitive, I saw some operations using high-pressure water cannons to wash away the lighter soil and leave the heavier minerals in concentrates that were then washed more carefully. In every stream, there were invariably workers using baskets to pan the gravel for gems. By long-standing custom, these streambeds and mine tailings may be searched by anyone. If gems are found, it's finders-keepers.

As was to be expected, I found a lot of evidence of clandestine mining. One day we traveled up a steep mountain trail for two hours. On the way up, I noticed numerous small-scale gem mining operations hidden in small valleys or perched on the mountain slopes. I was told many of these were illegal. That explained why several of the mines that we passed showed fresh signs of activity but were deserted. It appeared that the workers had slipped away just as our Jeep came within earshot.

As we came to the top of the mountains, the town of Mogok lay far below. We then crossed a rocky pass and made our way slowly through another high valley, where I counted dozens more mining operations underway.

This valley, Palin Guangko, is the source of some of Myanmar's finest peridot. One of the major operations, the Palin Zing mine, had just reopened after the rainy season (which lasts from May to October) and was being worked by 80 miners. While we ate lunch in a wooden shack, a sudden dynamite blast shook the ground. What was left of my appetite was killed when dust from the shack's roof fell onto our food. These charges were set without warning, and they were far too close for my taste. This valley, Palin Guangko, is the source of some of Myanmar's finest peridot. One of the major operations, the Palin Zing mine, had just reopened after the rainy season (which lasts from May to October) and was being worked by 80 miners. While we ate lunch in a wooden shack, a sudden dynamite blast shook the ground. What was left of my appetite was killed when dust from the shack's roof fell onto our food. These charges were set without warning, and they were far too close for my taste.

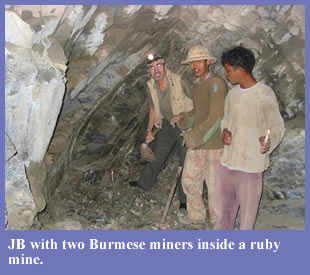

Later, I saw about 15 workers on the steep side of the hill sifting through the rubble from the blast. Down a short trail and around the other side of the hill, I entered a new tunnel, which had been dug out of the hard rock by a jackhammer. This tunnel was about eight feet high, seven feet wide, and extended into the rock for more than 25 feet. It was lit by candles and had no supports other than the timbers shoring up the entrance. Inside, two miners were searching in vain for a vein of peridot. Maybe someday, I thought, they'll find what they're looking for. Later, I saw about 15 workers on the steep side of the hill sifting through the rubble from the blast. Down a short trail and around the other side of the hill, I entered a new tunnel, which had been dug out of the hard rock by a jackhammer. This tunnel was about eight feet high, seven feet wide, and extended into the rock for more than 25 feet. It was lit by candles and had no supports other than the timbers shoring up the entrance. Inside, two miners were searching in vain for a vein of peridot. Maybe someday, I thought, they'll find what they're looking for.

But for the time being, it is safe to say that Mogok has seen better days. While it may continue to spark the dreams of the adventurous, the practical-minded can expect its gems to be in low supply and high demand.

SIDEBAR: SEEING RED

Myanmar is experiencing a dry spell of the gem for which it is best-known: ruby. That fact was clear when I visited the fabled ruby-mining region of Mogok in upper Myanmar in November 2002. And it was just as clear at the state-sponsored gem auction held last March in Yangon, the country's capital. There, everyone knew the decade of low ruby prices was over when parcels of fine ruby went for up to double their current value in Bangkok.

Paying sky-high prices for fine Myanmar ruby isn't an aberration but a reflection of reality. The world had been paying unrealistically low prices for Myanmar ruby since the discovery of a vast mother lode at Mong Hsu in the early 1990s. Prices fell further in the middle of the decade when it was learned that much of this material was "glass-filled" during heating to improve clarity. By late 2002, however, the abundance of inexpensive Myanmar ruby was disappearing.

Because of the scarcity of ruby in medium and better to fine qualities, expect to pay steeper prices for goods in the months ahead. Fellow dealers who recently went to Bangkok in search of fine, unheated goods returned empty-handed. It's not because they balked at paying the prices asked for such stones. It's because virtually none were available. Even finer heated stones were in thin supply. Because of the scarcity of ruby in medium and better to fine qualities, expect to pay steeper prices for goods in the months ahead. Fellow dealers who recently went to Bangkok in search of fine, unheated goods returned empty-handed. It's not because they balked at paying the prices asked for such stones. It's because virtually none were available. Even finer heated stones were in thin supply.

Demand remains high for top-quality ruby, which means Myanmar. As supplies continue to contract, expect to see a rapid shift from a buyer's to a seller's market that could carry fine ruby prices higher than they've been in more than a decade. - JB Demand remains high for top-quality ruby, which means Myanmar. As supplies continue to contract, expect to see a rapid shift from a buyer's to a seller's market that could carry fine ruby prices higher than they've been in more than a decade. - JB

|